Wh-at

Mrs. Bolshevik ordered the eight second graders of Holler, South Dakota, to write “goat” in cursive. And Mary, a girl who never felt brave, suddenly did. Instead of connecting the “o” and “a” with a straight bar, as demonstrated, she was about to connect the “o” and “a” with a curving loop. She had seen her sister Tabitha do it at home. Mary touched her chalk to the board.

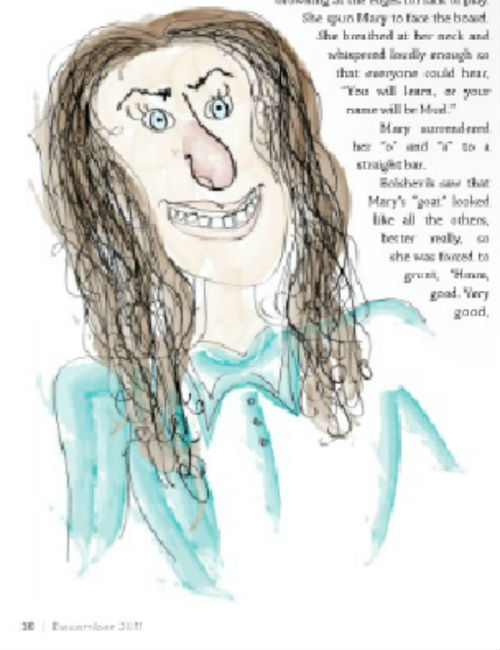

“Miss O’Grady, wait a minute!” Bolshevik pivoted her Weeble-Wobble body over to Mary. As she got closer, Mary felt crowded by Bolshevik’s nose: round, red, crater-filled and her teeth like old piano keys: long, yellowed, and browning at the edges for lack of play. She spun Mary to face the board. She breathed at her neck and whispered loudly enough so that everyone now finished could hear, “You will learn, or your name will be ‘Mud.’”

Mary surrendered her “o” and “a” to a straight bar.

Bolshevik saw that Mary’s “goat” looked like all the others, better really, so she was forced to grunt, “Hmm, good. Very good, Mary. Now sit down.”

Mary worried at her desk, flipping up the lid for her phonics workbook, whether anyone would wink at her before lunch. It was not a system they had taught each other. The winking game had just begun one day, like a new slang word catching on.

If a girl winked at you, it meant she wanted to be your playmate during recess, and your best friend the rest of that day. There were four girls in her class, including Mary. This meant that generally she was safe; she would exchange winks with someone, and they would shuffle through the lunch line together for their hamburger hotdish and cookies. She would go to the milk machine for them and come back with frothy glasses of two-percent. And then it would be four-square or hanging upside down in the entrances to the monkey bars, all the blood rushing to the head until you were tingly everywhere.

But today one of the Ashley’s was gone. Since attendance had been taken, this had gnawed at Mary. Usually one came when mid-morning hunger pangs began, and you remembered recess was on its way. But phonics was starting—ten o’clock, and Ashley K. and Mischa had barely made eye contact with Mary. She rarely initiated a wink, always wondered, would want to pick her? But she was panicked. She began trying to catch their glances. Had they already winked at each other? It would explain the dry spell. They each sat in the second seat back in three consecutive rows. Mary was on the far right. She kept her head faced left to get their attention. But they didn’t turn. Mary began feeling dizzy. She looked down at her workbook page and then up at Ashley K. and Mischa.

Mrs. Bolshevik pursed her lips and pronounced “wh-at.”

“Notice, you hear the h, too, not just a ‘w’—‘wh-at.’ Now you do it.”

“Wh-at.”

Now Mary had to look at Mrs. Bolshevik, too, and scratch checkmarks onto each “Say-It-Yourself” blank. And search out. But they sat focused on the lesson. Mary couldn’t take it.

“Ashley,” she whispered.

“Wh-at,” they all repeated with Mrs. Bolshevik. Ashley K. swooped her eyes Mary’s way. Mary winked so obviously that her head nodded. But Ashley K. didn’t see. You never asked someone to play with you, with words anyway. Just winked—that’s all.

“Wh-at,” the students repeated again. This time Ashley K. said it like a question and turned to Mary.

Mary winked again, but this time forgot to say the word. Busted.

“Miss O’Grady, you don’t need to practice, huh?” Mrs. Bolshevik barked. “You’re perfect? … I guess you’re ready for the oral test, then. C’mere, Mary.”

Mary hesitated. A little hole had begun in the crotch of her pants, which were snug. She didn’t want anyone to see.

“C’mere! With your book, Miss O’Grady!”

Mary clutched her book like a shield and tip-toed to the front.

“Sit right here.” Bolshevik pointed to a wooden chair she had plunked front and center. Mary clamped her legs together.

“Get your book open. Read that list, fast as you can.”

Mary read them—in her head. She ripped through each verb: walk, whip, whisper, write, wilt—

“To the class, Mary!”

“Walk … Wh-ip … Wh—“

“Faster!”

“Wh-isper, wh-isk, wirl—”

“Wrong! I can’t hear the ‘h!’”

“Wh-irl, wh-ilt—”

“Wrong! There shouldn’t be an ‘h!’”

And down the list, until tears blurred the w’s and h’s, and Mary couldn’t decipher them anymore.

“In the corner, Mary! If you can’t keep from begging Ashley K., you won’t sit by her.”

Mary moved. The heater blew furiously next to her like river water crashing into boulders downstream. She couldn’t hear Mrs. Bolshevik but could still see Ashley K. and Mischa who stared, like everyone else.

Mary quickly rubbed her eyes dry and smiled. She winked at Ashley K. But she looked down and shook her head.

Ashley K. looked up. Mary winked again. Ashley K. winced and mouthed, “No.” The river carried Mary further and further away, so she reached out in one last attempt to Mischa, who might still pitch Mary the lifesaver circling her pupil. Mischa shook her head, too, though, with such certainty, and her lips formed “wh-at” with such force that she pushed Mary beneath the current. You’d have thought she had never played with Mary before, that she had never seen Mary before. Fact was, everyone turned to Mary gawking, not even sure “wh-at” she was.